Children first hear phonemes without seeing the graphemes, through phonological awareness activities. Therefore it is only natural that the sounds are first linked to the actual graphemes rather than the names. However, ensure that learners understand they are being taught the phonemes (sounds) and not the names of the letters as these need to be taught separately.

The best time to introduce the names of the letters is when digraphs are introduced, because the letters are going to be making a different sound in the digraph and therefore should no longer be referred to as the phonemes (sounds) or there will be confusion, especially when saying what letters to use to spell larger or tricky words. A grapheme can contain one or more letters, but produces one phoneme (sound).

When introducing the names of the letters, it is a good idea to mention to the children that so far they have been learning the sounds/phonemes of the letters, not the names. I find it helps the children to understand by reminding them that younger children may have referred to a dog as a ‘woof woof’, or a cow as a ‘moo’. Explain that the ‘woof’ is one of the sounds a dog makes, but the name of the animal is always ‘dog’ and similarly ‘moo’ is one of the sounds a cow makes, but it always has the name ‘cow’ (have toy animals there to help them visualise this) and as they get older they start to realise this. Similarly, all letters have a name and can make one or more sounds, one of which the children have already learned. Introduce an alphabet song for the child to join in singing slowly and clearly whilst pointing to the letters. Gradually point to a random letter and ask what is the name of this letter, then what is its phoneme (sound).

It is a year 1 curriculum objective to be able to name all the letters of the alphabet as well as say their phonemes. Therefore, by the time a child is in year 1 it should be common practise for adults to use the letter names when talking about individual letters rather than the sound and the learners should also always be using the names of the letters instead of the phonemes when talking about what letters to use in order to distinguish between alternative spellings. Learners should use an alphabet arc and practise saying the names of the letters whilst touching each letter in turn. They should then be asked for individual letters, what is the usual phoneme for this letter? By repeating these activities, the responses become automatic which will help with grapheme/phoneme correspondence.

The ‘Phonics Queen’ has made a great video to help explain the difference betwen graphemes and phonemes and demonstrate the pure sounds to be used, as shown below.

Also, children need to learn wow to order the letters of the alphabet, to help them with sequencing, using dictionaries, contact lists etc. They should learn that there are 26 letters in the alphabet, but 44 phonemes that the letters can make. Working with the letters also helps the children become more familiar with the letters as the shapes become more recognisable.

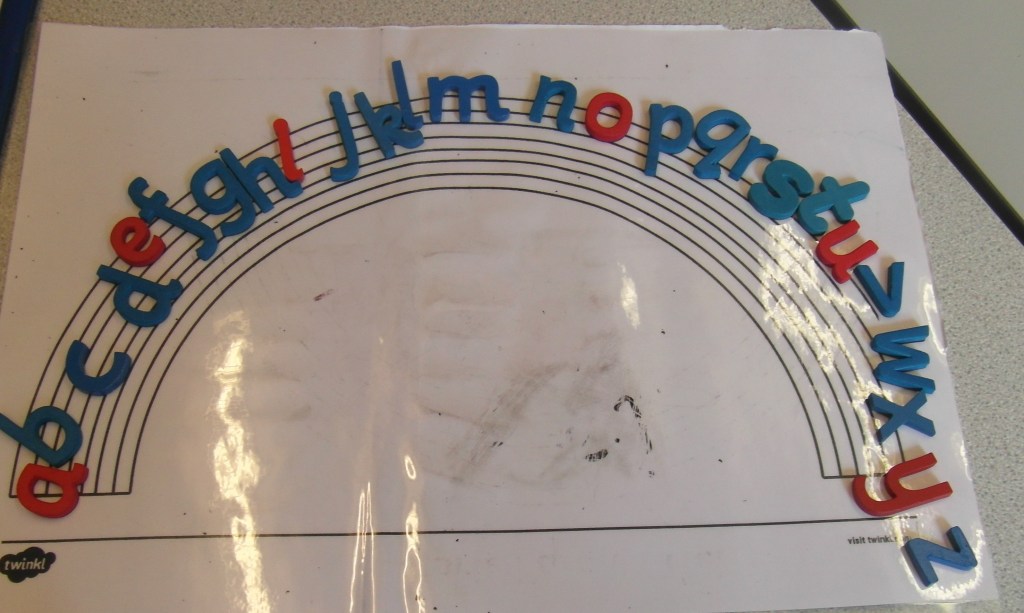

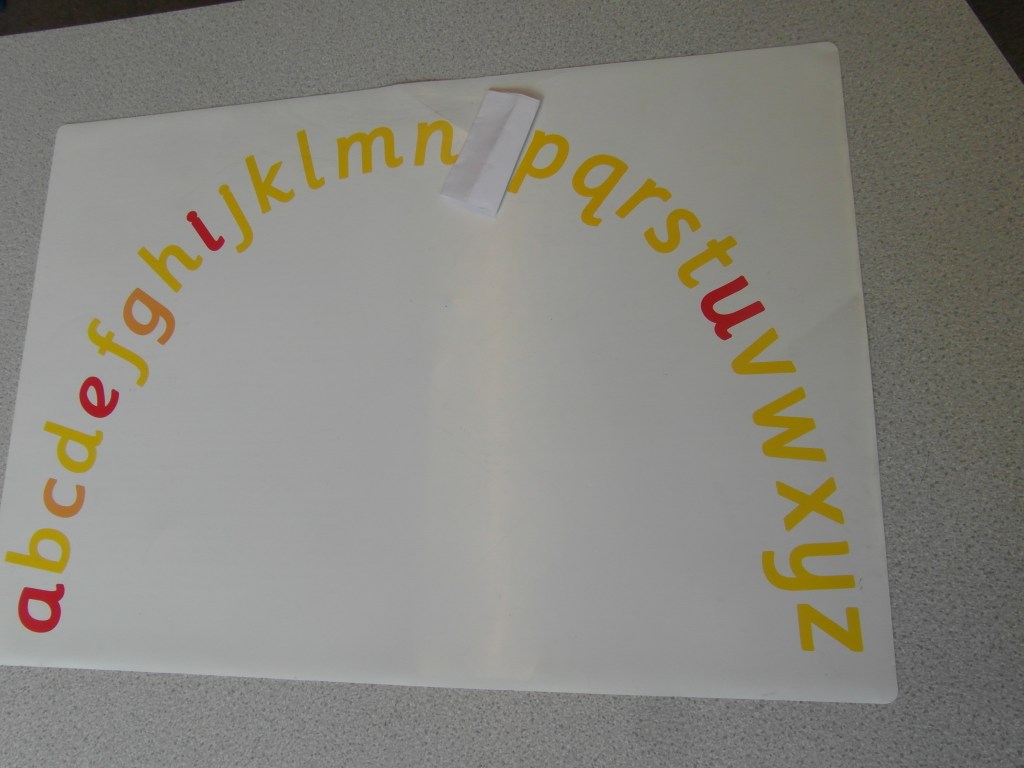

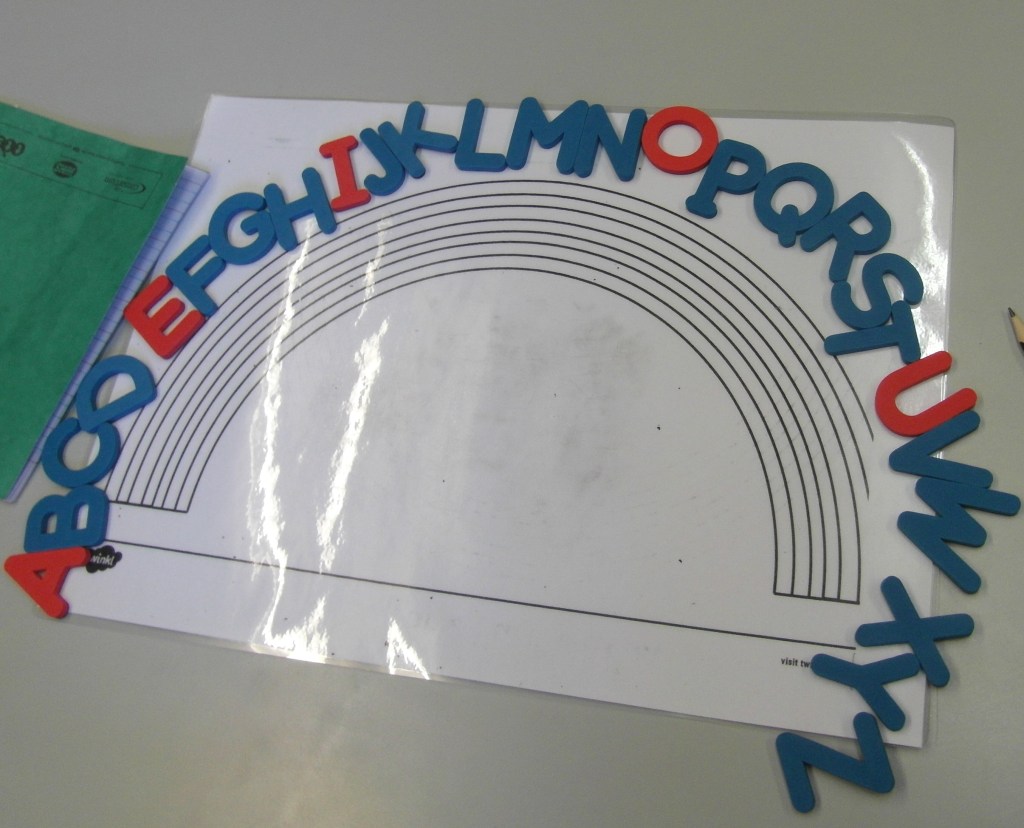

Learners are best to use magnetic or wooden letters to have multisensory learning and they should order the letters in a rainbow shape, (alphabet arc) so they can see easier where the letters come in the sequence i.e. the letter ‘m’ will be placed in order at the top of the rainbow. This will help the learner to remember that the letter ‘m’ is halfway through the alphabet. Similarly they can tell on the arc in which quarter each letter can be found. An alphabet arc needs to have vowels in one colour and consonants in another, as this will reinforce that each syllable has a vowel in it when making words with these letters. Children can learn at first to match the letters to preprinted letters on the arc and then gradually, when they are confident, start ordering the alphabet without the hints. Learners need to start from the letter ‘a’ and work their way around the alphabet in order to reinforce in their visual memory where the letters are on the arc.

Letters from the alphabet arc can be taken from the correct place to make vc words at first on an Elkonin frame (basically boxes to separate words into phonemes). The learner will get used to taking the letters from the correct place in the alphabet and putting them into the Elkonin frame, noting that there is a vowel in the word. Then the learner needs to replace the letters into the correct place on the arc. Similarly the learner can move onto cvc words and then longer words by using more phoneme boxes to place the letters in. They will take the letters from their place in the alphabet arc and return them when completed.

Letters can be hidden and the learner has to say which letter is missing or a sequence of two letters can be shown and the learner needs to say which letter would come after them in the alphabetic sequence and which letter would come before them.

Useful, affordable sessions about using the alphabet arc are regulary scheduled by http://www.sendstation.co.uk.

As well as practising making the alphabet with wooden or magnetic letters, there is a useful interactive alphabet arc online where learners can practise quickly without having to get out the wooden letters and this can be found on: https://dl.esc4.net/rla/alphabet-arc/english.html However, access to this seems to be limited at the moment, so as an alternative there are moving alphabet tiles that can be used on https://www.edshed.com/en-gb/LetterTiles

Children need to be able to match up the lowercase and uppercase (capital) letters to ensure that they realise that these letters make the same sound and have the same name. There are various matching games that can be used e.g. pelmanism when a set of capital letters and a set of lower case letters are written on cards and placed face down so the learner has to match up the capital and lower case letter – just use a few letters at a time. The capital letter alphabet arcs should also be practised with capital letters and similar games played to find the missing letter.

Vowels

The five vowels in the English alphabet are: a, e, i, o and u. The letter ‘y’ is a semi vowel as it sometimes makes the same sound as a vowel. All vowel sounds are open, meaning when they are articulated, nothing is blocking the airflow. The vowels are all voiced sounds, so the vocal cords are used to make their sound; we can check this by either feeling the vibration of the vocal cords on our neck as we say the sound or (and I prefer this method) we can try and alter the pitch of a sound and if we can do that, it is a voiced sound. There is at least one vowel in every word because there must be a vowel in each syllable (the letter y is a semi-vowel and classed as a vowel when it makes a vowel sound e.g. in the words my, rhythm, funny). The vowels can make long, strong sounds as in pāper, hē, hūman, pīper or short, weak sounds as in căt, shĕd, trĭm, sŏck, ŭnder. It is important that learners understand which letters are vowels and the difference between the short, weak sound they can make and the long, strong sound, because spelling rules often depend on what sound the vowel is making.

Consonants

There are 26 letters in the alphabet, 5 of them are vowels and the rest are called consonants. Most consonants will only have one sound when they are used on their own, except for the leters ‘g’ and ‘c’ which will change their sound if followed by the vowel sounds made by the letters i, y or e. Usually the letter ‘g’ makes a /g/ sound as in goat, but if followed by the letters i, y or e it will make a /j/ sound as in gym, giant, gem. Similarly the letter ‘c’ usually makes a /k/ sound as in cat, but if followed by the letters i, y, or e it will make a /s/ sound e.g. ice, cygnet, circus. Consonant sounds are usually blocked or partially blocked by the tongue, teeth or lips. Most of the consonants are voiced, but some are unvoiced such as c, f, p, s, t and to make the pure sound of these voiceless consonants, no vocal cords are used, only the air in the mouth is used to make the sound by changing the shape of the mouth or using the tongue.